Magic comes from a place unseen and untouched that perhaps hangs draped over Seth like a veil, or perhaps suspends it as a limpid pool, or perhaps spews out of people’s mouths when they talk and breathe, and their eyes when they see.

Magic loathes the mundane, and magic changes things in direct spite of the mundane’s states and laws.

Under magic’s design, the properties of things change, shapes change, matter bows to concept, logic bows to intuition.

One might cast a spell, an instance of magic, and remake the stuff around them as they please, but one does so at great risk: magic enters into the mundane through the body, which, more than likely, is mundane itself.

Do not forget! Magic loathes the mundane.

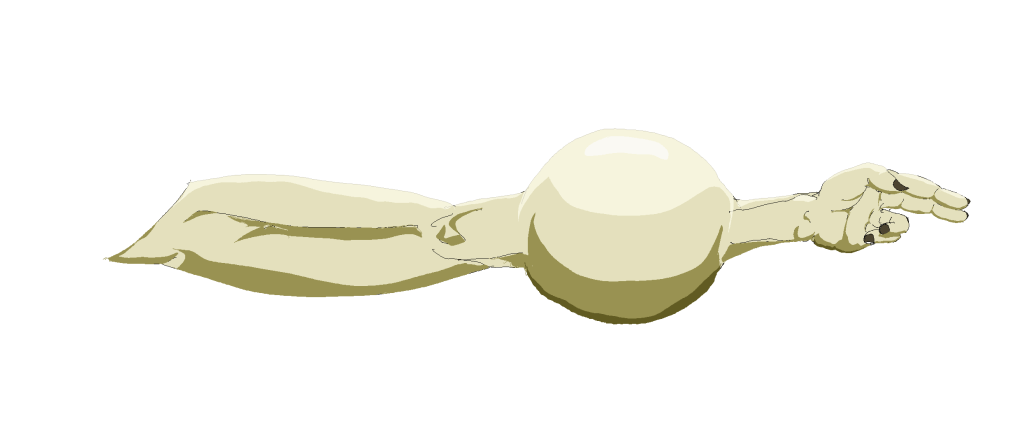

As it travels through, it must be reckoned with accordingly, composed appropriately, otherwise it will present itself prematurely and wreak itself unchecked upon the surrounding tissues. A lapse in technique can and will cause random mutation.

A minor spell, miscast, might result in little more than some bruising, but could just as easily cause a fatal blood clot or creeping organ failure. A more demanding spell will have itself out in the guise of massive, sudden tumescence, deep, oozing fissures, new, inopportune appendages and organ systems, skin turning to teeth and teeth turning to skin, so on and so on, almost always with immediate lethality.

In a near-unmentionably small percentage of cases, these more dramatic mutations are functionally ‘neutral’, leaving the caster alive, if not with some tell-tale disfigurement or malady. In even fewer they are beneficial.

So what is it to cast a spell? It must be deliberate.

It cannot be by breathing, or walking, or eating, or blinking, or shitting, or bleeding.

It might, however, be by breathing, or walking, or eating, or blinking, or shitting, or bleeding, in a certain way, by engaging in any act with intent and form detached from that necessary for one’s immediate survival. In other words, by exercising one’s sapience.

Language, then, is the most common substrate for spellcasting, spoken and written alike, but there is no act so abstract it cannot become a vehicle of magical intervention. Such as it is, the magical lexicon of a given people is a fundamental aspect of their culture. Their stories, their tastes, their preferred rhythms of song, dance, meter, thought, of lines painted, carved, and hammered, all inform and are informed by the magics they bring upon themselves:

Among the Vranque, the Cloistrium of Tor may observe their surroundings as if they are thirty metres tall, but first must inhale slugs of blessed incense according to sequences set by one of Canta’s holy choirs.

The treasured archaeomythril worn by Mythogenian labyrites, bearing glyphic accounts of epic chapters older even than the language they speak, is nigh-impervious to mundane forces, but without said friezes would be little more than sheets of tarnished metal.

The zzizwar, the elite bodyguard of the primordial Mattersnake Yemma-n-Uzrem’s polar hoards, can cut through steel despite wielding blades and switches of far weaker materials, trained to do so by repeating that same strike, perfect to the degree, no less than two hundred and seventy-nine thousand, eight hundred and forty-one times, all while standing barefoot on an ever-shifting bed of red-hot sand.

There is no one not touched by magic. Magic follows everyone, without exception, as if it is in love, as if it seeks to free them from the mundane. It is always lingering, and never hesitates to express itself.

Even those who claim to shun magic, who fear it, who decry spellcasting for its capricious and wanton inclinations, are carriers of magic. This is the ‘mute’, ‘muscular’, or ‘marrowing’ magic, that creeps into the bodies of all Sapients. It attaches to any moment of practice, whether the intent is towards spellcasting or not, contributing to the effort and raising the bar of its potential. The distinction between physical excellence or artistic talent and magical enhancement is thereby non-existent. Veteran warriors are not just hardened figuratively, their bodies have taken on greater strength and resilience than should be offered by their biology. Virtuoso musicians actually cause magical changes in their listeners’ physiology, and even their environment. The humble clerk, confined to their desk, after years of work can write, calculate, and assess at speeds double that of their counterparts in our own world. This magic is far less potent than that used to cast an actual spell, and has its own limitations, but comes with no risk of mutation.

One who exhibits traits realised in this way is often referred to as ‘well-marrowed’.

Another common, non-casting form of magic is that of the shepherd, the keeper. This magic is similarly diminished or subtle to the above, but goes a step further as it travels through the Sapient subject into the bodies of animals. Over time, an individual may form such a strong, marrowed bond with a beast that the two begin to share of sense and even thought. The Sapient’s body becomes more attuned to the environment, following the concerns of their companion, and the beast gains a higher level of cognition, able to follow complex instructions and solve problems. At the highest levels, the two can engage in semi-fluent conversation, sometimes even without speaking. This is a phenomenon that exists in nearly every culture on Seth, and names for it are myriad, but it will generally be referred to as ‘mutuality’, and both Sapient and bestial components as ‘steers’ of each other.

This serves as an introduction to the most prominent and reoccurring modes or ideas of magic on Seth, but is necessarily feeble given the twice-infinite possibilities of magic’s entry into the mundane, and its effects therein.

Leave a comment