The Elves of Syzygos are a people of two distinct yet united halves.

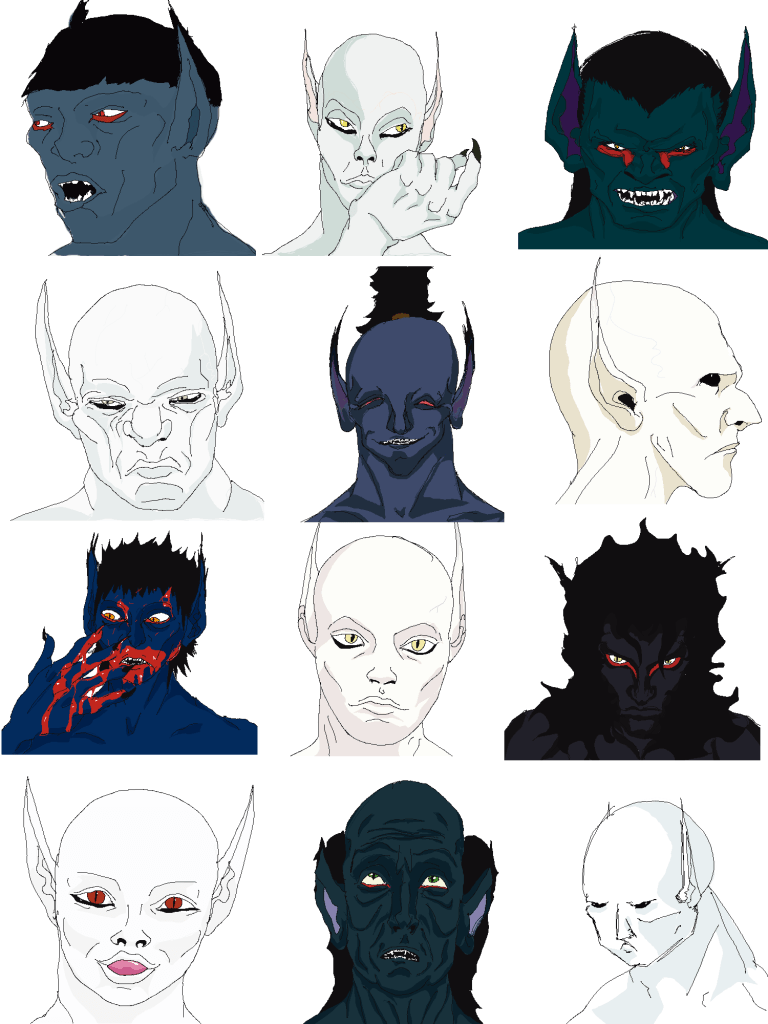

Each Elf is born into one of two phenotypes known as ‘optomorphs’, called ‘High Elves’ and ‘Low Elves’ respectively.

These optomorphs are so immediately different from one another that it would not be at all unreasonable to think them two separate species, but they are indeed one and the same, and it is only a couple of, admittedly important, surface features that distinguish them. The rest of their biology is shared, and it is these shared traits that we will explore first.

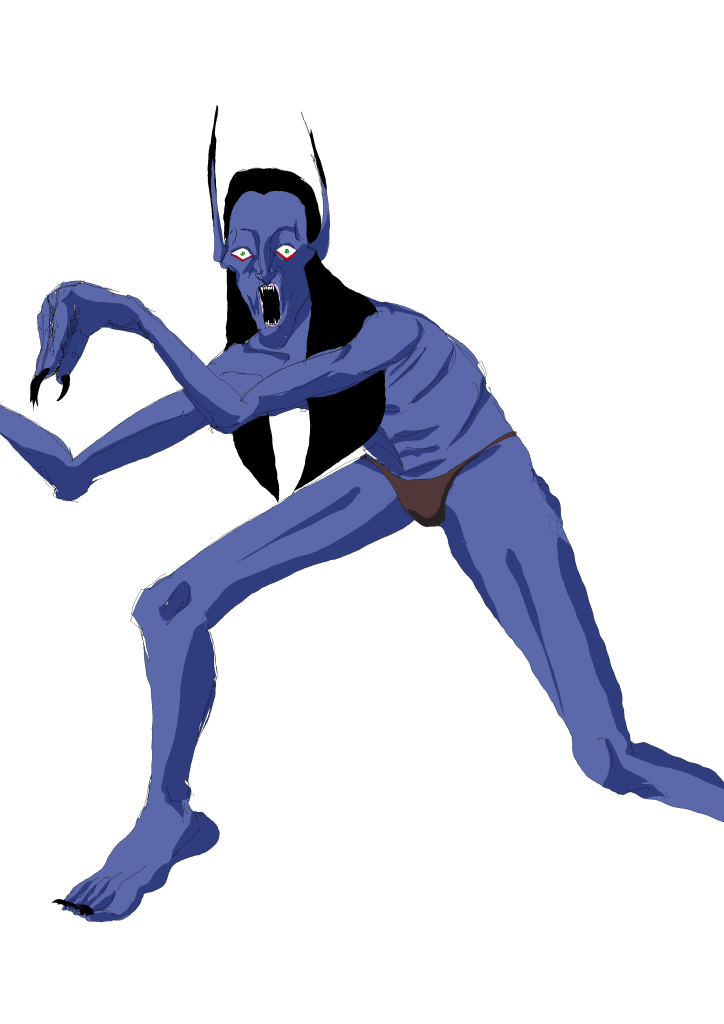

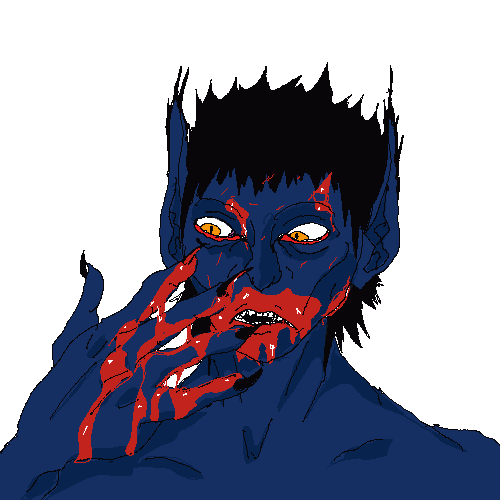

Elves are tall, among the tallest of the Sapients, with an average height of 6’5. They are bipedal tetrapods with flattened faces and forward-facing eyes, something shared by nearly all Sapient species. Pointedness is the form of the Elf- their ears,noses, teeth, claws, pupils, and faces are all long and sharp.

They are blessed with a naturally muscular, svelte build, wrapped around a deceptively sturdy frame, all working in concert to achieve an impressive combination of speed, strength, flexibility, and reflex. They are the fastest sprinters of the Sapients, and possess some of the highest jump distances and lowest reaction times also.

Sexual dimorphism is minor at best. Females have some mammary tissue and a slightly wider pelvis, but are otherwise indistinguishable in stature and appearance.

Their long limbs end in digits armed with fearsome, hooked claws. These consist of a bone core surrounded by a constantly-growing keratin sheath, and were at one point in the Elves’ evolutionary history completely retractable. Now, however, the system of tendons and musculature that facilitated this movement has become ossified and packed together to lend the fingers more strength as they have lengthened, although there is still a leftover ‘lifting’ reflex that allows an Elf to close their hands and manipulate objects with the pads of their fingers without their claws getting in the way, and to keep the claws on their toes sharp by raising them above the ground. These claws are useful as tools and weapons alike, and are kept in best shape by frequent use.

Second in the arsenal of the Elf are their teeth, and the jaws that house them. At the front of each row, themselves mirrored in the top and bottom jaw, sit four wedge-shaped incisors, designed to aid in shearing and purchase. Next are the canines, eye-catching and prominent, relatively enormous, particularly the mandibular pair, which extend down past their lower siblings, and act as the killing-tools. Behind these are seven carnassial molars, brutal, stocky, and crowned with interlocking blades that sharpen themselves against each other with the motions of chewing.

To put these teeth to their proper use, the Elf’s jaw is both versatile and powerful. Elves have the widest mouth gape of the Sapients, relative to their skull size, able to open their mouths to an average of sixty degrees, allowing them to wrap their teeth around large objects, and swallow huge chunks of food. This flexibility does not compromise on power, however. The zygomatic arch and mandibular bones are elaborately developed to support the masseter muscles around the jaw, allowing it to snap shut with maximum power- around five hundred pounds per square inch, sufficient to crush bone- even at full extension. These muscles connect to a similarly well-developed set in the neck, adapted to absorb the force of struggling prey. Even so, Elves must be careful with their teeth, as they only get one adult set.

In order to veil all of this machinery, Elf lips are wide and supple, hanging in a characteristic sneer.

The cranial senses of an Elf are formidable. Their eyes, noses, and ears are all large and well-developed, every cell dedicated to function. Their slit pupils let in light from all wavelengths, and are backed by a retroreflective tapetum lucidum, allowing them to see well in any lighting conditions, as well as giving sharp image and depth perception. Their nostrils pull in large amounts of air to cross over sinuses that are wide and spiral-shaped, increasing their surface area, picking up scents from hundreds of metres away. The fleshy outer parts of their pointed ears snatch soundwaves like daggerish aerials, and the vestibular system housed by their inner ear is large and delicate, offering balance and agility.

If it has not become obvious by now, Elves are adapted as hunters, predators. They are hypercarnivores, their diet consisting mostly of meat, and in order to maintain body-weight, they must consume upwards of three thousand five hundred calories a day.

Here is where it becomes pertinent to speak of the optomorphs:

Elves, despite their apparent ferocity, are among the smallest animals to emerge from Syzygos, outmatched in size across all major niches, even by their preferred prey, one mature individual of which weighs as much as ten Elves.

As such, in order to meet their caloric requirements, they have adapted for a specialised, almost eusocial form of pack hunting, where each of the two optomorphs takes up a distinct position in the canopy of Syzygos’ dense, sky-scraping forests. Their names correspond: High Elves are designed to occupy the branches of trees, Low Elves to stalk through the undergrowth. In doing so, the pack claims both niches in order to better advantage itself against what would otherwise be overwhelming odds. In aid of this, then, the differences between High and Low are found in their eyes and their skin.

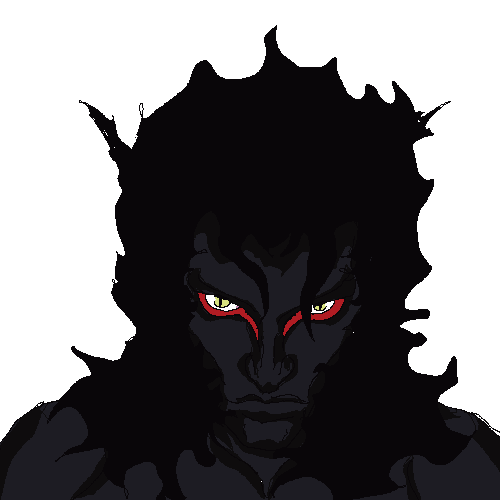

To start, Low Elves are distinguished by a covering of short, dark hair or fur often referred to as ‘suede’ for its smooth, dense texture. Atop their heads grows longer hair that if left to its own devices takes on a mane-like shape, travelling down the back of the neck. Their ears, too, are crested with similar hairs, making them appear longer still.

Their eyes rest upon crescents of bright red flesh that at a glance may look like tears of blood. Rather, these are a modified third eyelid, an aperture of muscle that travels along the lower edge of the eyeball and down the outside of the nose. This can be opened or flexed to reveal a bright red membrane that is packed with highly sensitive, specialised nerve clusters designed to receive heat information via air pockets in between the membrane and the skull. This membrane is connected, by way of an extremely elaborate nexus of nerves and blood vessels, to the eyes, and engorging it allows the Low Elf to ‘see’ thermal patterns, in the manner of an infrared camera or the dimpled snout of many snakes.

This organ, known as the ‘pitgroove’, allows Low Elves to accurately track living targets even through dense vegetation and total darkness, with a functional range of about twenty metres. However, it can only be engaged for brief periods of time before it becomes stressed, causing intense migraines, and, if overused, becomes worn-out, dry, and painful.

Their suede, and the hair on the tips of their ears, grows out of a tight net of mechanoreceptors that gives it a similar function to whiskers, sensing slight changes in air pressure and alerting the Elf to nearby movement.

As such, Low Elves are adapted to close range ambushes, sensing targets from behind cover, and tracking them until they are in an ideal range to strike.

Selection of these targets, however, is the work of the High Elves. They too have a third eyelid, but theirs is instead confined to the length of the eyeball itself. A deep black in colour, when flexed it flicks up over the rest of the eye, like a pair of organic clip-on sunglasses.

Rather than block light from entering the eye, however, this eyelid functions as a powerful, telescopic lens, greatly increasing the maximum distance that the Elf can see. It even has an internal ring of muscle that allows for a limited ‘zoom’, and at its most extreme can allow a High Elf to pick out small objects over fifty metres away. From their position in the canopy, then, High Elves would scan the surroundings for prey or its traces, moving from tree to tree until they spot something promising. Like their counterparts, reckless use of this eyelid, the ‘seeing-eye’, has its risks. The seeing-eye’s are more severe than the pitgroove’s, however, as the increased amount of light it causes to be absorbed into the eye can quickly cause blindness, not unlike staring into the sun.

In aid of wide-range scanning, then, the High Elf’s skin is completely devoid of hair. Instead, in place of mechanoreceptors are chemoreceptors, microscopic pseudo-olfactory cells that pick up on scents. Individually, they are dull, but spread across nearly the High Elf’s entire dermis, they are able to trace odours carried upwards on the wind. This system is far from an exact radar, and some stillness and focus is required for its proper use, but it is always the first sense deployed in the hunt.

As such, the model formation of an Elf hunt is as follows:

The High Elves ascend to a comfortable altitude, their claws making light of the task. Here, they ‘sniff out’ potential targets with their skin, and, if close enough, their noses. They move as a group, spreading out to maximise their coverage, periodically inspecting the ground below with their seeing-eyes.

The Low Elves follow along, usually lower in the canopy, with equal ease to their counterparts, until game is spotted and a catch selected. Then, they descend, guided from above by the High Elves, usually by way of calls and whistles, until the target is in their own range of sight, and close in.

What happens next is specific to each hunt, but usually entails the Low Elves making the first move, ambushing the prey and aiming either for vital spots or to disable its movement. The High Elves, then, rain projectiles from above, prepared to track the beast if it is able to escape, or leap down and offer more direct support if it overpowers the team on the ground.

What has been described above is an ideal situation. The quarry that this method evolved to ensnare is large, and if it is not a herding animal, likely well-armoured. An aggressive individual can easily turn and drive off its hunters, especially if they overextend themselves. This is not to mention the threat of other hunters in the area, miscommunication, environmental obstacles, meddling spirits, nor the greatest danger; large scavengers and kleptoparasites that can make an easy meal out of an Elf kill, and will invariably be summoned by the scent of gore if a hunt becomes too drawn-out.

Elves are not merely brute predators, then. They are highly social animals, and this too is written into their biology. Their optomorphic traits are used heavily in communication, each morph having their own quirks that appear different, but are brought about by the same stimuli.

Engaging the eyelids is a common, often involuntary, response to heightened emotion, particularly aggression and fear. The eyes themselves widen in curiosity and affection, and expansion of the pupils is a telltale sign of great interest in something.

The ears are semi-articulate at the base, and twitch and flex to express such feelings as disinterest, amusement, or worry.

Embarrassment, anger, hilarity, and arousal flush the skin’s myriad blood vessels, causing an erecting, ‘hackle’ response in the hair of Low Elves, and a clear ‘blushing’ in High Elves. As an aside, each High Elf has a unique pattern underneath the skin that shows during this response, and if one were to have the opportunity to shave a Low Elf, one would find the same.

All these are used in the day to day communication of the Elves, but there is no time that is as rife with emotion, and sees as many Elves congregate, as the yearly time of ‘Heat’.

Both male and female Elves have a concurrent hormone cycle, that, annually, following the fattening season of prey animals, causes a month-or-so long state of spiked fertility and libido. This period is marked by greatly increased activity, sexual desire, and appetite, usually resulting in far more frequent, and often dangerous, hunts.

Elves are inclined to select mates based on physical prowess, and it is during these hunts that such prowess is demonstrated, hence their recklessness. They trend also towards monogamy, forming strong bonds, but in reality do not mate ‘for life’ more or less than anyone else, and although packs usually organise themselves into social and leadership hierarchies ordered by couples as single units, this balance is far from immutable.

This is not to say that Elves are sexless for the rest of the year- they are still subject to desire, just not half as much as during the Heat.

The effects of the Heat wane with age, until a point when it is effectively non-existent, and fertility plummets in both males and females. This marks the beginning of true old age for an Elf.

Elf pregnancies are short, and although the mother’s mobility is diminished in the later stages, early on she can actually slow gestation deliberately, biding her time until conditions are more ideal. However, delaying by too long can cause birth defects or even miscarriage.

Generally, only one child is born, with twins being a very rare exception.

Elves are born highly altricial- tiny, hairless, blind, and barely even capable of sound or movement. However, they grow quickly, gorging on milk for a year or so, and can walk nearly as soon as they are weaned. At this stage they are not quite ready to climb, and so must be carried by their parents for another year or so until they are ready to support themselves across the air and branches, or until they are too large.

Many Elves can scale a tree and leap from its boughs before they can even form a sentence. Growth after this stage is steady, until a fierce spurt at around nine years old that usually sees them reach near their full adult height, imparting a telltale, adolescent lankiness. These adolescents are light and nimble, if frail, and are usually employed as lookouts. Then, growth is at its slowest, with muscle and bone taking their time to consolidate into their mature form over the next decade.

Around two thirds of the way through this growth is when puberty strikes, and the young Elf experiences their first Heat- often a thoroughly disorienting experience, and one they must learn to reckon with.

Neural development continues, slowly, as the brain must be tempered by the Heat cycle before it can become properly mature.

Heat is not the only sudden hormonal change in the Elf’s biology. It is mirrored by a far more sinister, dangerous, and immediate state: ‘Ferality’. Also called ‘Bad Heat’, ‘Hunger-Walking’, or, simply ‘The Madness’, it is a lurking possibility within the body of any Elf.

Essentially, when an Elf has not eaten for a certain amount of time (usually two and a half days), their brain chemistry undergoes a rapid change, causing them to become extremely aggressive, and does not cease until they have consumed at least twice their daily caloric minimum.

In this state of Ferality, their body drains completely on its last reserves of stored energy to produce huge amounts of adrenaline. Their speed, strength, and reaction times become sharpened to a point, but any cognitive function is severely repressed.

They will attack any creature within reach, including family members or animals many times their size, and cannot be reasoned with, only restrained, fed, or incapacitated.

If they are not sufficiently sated within a day, they will fall into a deep coma and soon die of exhaustion.

Those Elves who have recovered from Ferality are often quite severely traumatised, and must undergo a period of physical and mental recovery, with telltale signs such as shivering, loss of fine motor control, and disordered speech. This usually only lasts for a matter of days, but in some the symptoms never fully leave them, and for many the shock of their actions and their memory of the event itself leaves an indelible psychological wound.

Elf children are particularly prone to Ferality, and although they do not suffer as much as their adult counterparts, they can still receive lifelong disorders as a result, the trauma burning deep scars into their developing nervous system.

From all of the above, it may seem that Elves are unstoppable, ravenous killing machines. This is far from the truth.

Elves are well-adapted to their particular evolutionary mode of hunting, but this is a lifestyle made replete with risk by their environment, and until the development of sapience, they were more or less a footnote in the ecosystem.

Physically, Elves are strong and fast yes, but they are not designed for long engagements, and tire quickly. This, combined with their extremely fast metabolism and limited diet, means that they are unreliable in situations such as long-distance travel or extensive manual labour.

Their senses are exquisite, but this means they are easily dazed or even injured by sudden increases in sound or light. A blow to the face is also extremely compromising for an Elf, as their myriad sensory organs are fragile, and the bones surrounding them can be fractured easily.

As they leap through the trees, they are competent, but by no means perfect, arborealists, with climbing actually being one of their later developments. If they fall, they have an instinct to relax, which can reduce injury, but it does not guarantee survival.

It must also be stated that what has been described here is only Elf biology, not culture or behaviour. Sapience, as the reader will be well aware, has a habit of resisting biology, and seeking new solutions that render adaptations redundant. Although the High/Low hunting style is the model by which the optomorphs were prompted to specialise, in, say, an agricultural society, it becomes a sport, not a necessity.

Elves must navigate the states of Heat and Ferality, but they are more than capable of understanding them for what they are. In other words, something they can have an attitude towards, a philosophical and ethical standard relating to.

Elves might be cruel or kind. They might be anything. This is what it means to be sapient, and is something to remember going forwards as we explore the biology of the Elves’ six fellows.

Leave a comment